If you work in the genomics field, I have written this to confront dogmas and stretch your imagination.

(Part 2 of 2. To see Part 1, click here.)

The association of a person’s genotype to their traits are generally better for traits that are health-related than those that are not health-related. We have a better sense of what variants are implicated in breast cancer than breast size. This makes sense given the focus of funding in biomedical research. However, translating health-related content into DTC products have been difficult because a DTC healthcare market hasn’t materialized meaningfully yet. I expect that it will, and this area will continue to be developed. But I previously wrote that until then, the next wave of DTC products could focus on delivering entertainment, without being held back by doubts of the predictive value of the test. Customers may be willing to engage with “sunshine” genetic tests that focus on the enjoyable aspects of genetics that don’t need to provide any guarantees on its predictive capabilities. With this angle, entrepreneurs can focus on validating new products and markets, rather than validating the science, which for nearly all traits – especially multifactorial and polygenic ones – will almost always have flaws anyway. Therefore I propose this framework to create DTC products in genomics: they need to be leaner, cheaper, and multiplayer.

Leaner

New product concepts in the DTC entertainment category could sound outrageous. The problem with novel ideas are the lack of evidence of whether the product should be built. Therefore lean startup methodologies need to be employed, similar to how new tech products are developed. Frameworks given by Steve Blank, Eric Ries, and Alberto Savoia are useful starting points.

The customer “job to be done” should be clarified and a DTC product shown to meet it, validated through prototypes or other mock-ups. Once proven, the test should focus on delivering only that. Delivering a narrowly-focused product is sometimes counter-cultural in the genomics industry, where there is the temptation to build products that generate more data for future use. This could be useful for more complex business models but for simplicity I won’t address this here, and assume that all data should be deleted as soon as a result is produced for the customer.

Cheaper

Getting data as cheap as possible is essential because customers have a limited frame of reference for DTC genomics products. Starting cheaper will allow customers to give it a go, preferably at prices lower than $100. This has worked for ancestry testing, which incidentally is also priced appropriately for gifting.

Is it possible to sell tests at lower prices without sacrificing profitability? Genomics is sometimes and unnecessarily synonymous with next-generation sequencing. These assays costs 100’s of dollars. While the ability to sequence wide and deep is useful for research and diagnostics, in an entertainment setting where the stakes are low this is not necessary. Until these costs drop significantly, technologies that detect the bare minimum number of variants should be used. This could be through low-plex SNP assays, low content arrays, or low-pass sequencing, using imputation as needed. These assays could cost as low as 10’s of dollars, and a good reminder of why 23andMe might have stuck with arrays. Combined with deleting data after producing a result, the minute amount of data produced may help ease concerns on privacy.

Multiplayer

Taking a key trait that customers might be interested in then producing the result for a low cost allows an entrepreneur to focus on the user experience of how the product is ultimately consumed. For many existing DTC genomic products, this has been a report of some kind to be read in private. This stems from the legacy where genomic results are confidential, serious, and the result themselves elicit a strong reaction from its owner. Because the results for non-health DTC tests have weak predictive values, it won’t be delivered with the same gravity. Therefore if the reception of DTC results remains this lonely, dour endeavour, the customer experience and social utility will be limited.

Entertainment genomics should be fun and associated with doing things with others. Using gaming as an analogy, DTC genomics has mostly been a single player game. Instead, it needs to help the customer engage their friends and make it a multiplayer experience.

Imagine a product where the traits should be shared and misinterpreting them is part of the experience. If social media users are looking to share interesting discoveries with their friends, results of entertainment DTC products should be designed for increasing engagement (e.g. picture or video format), re-posting, and commenting (encouraging disagreement and re-interpretation). Consumers enjoy having using novel content to engage with their friends and family around a dinner table, or friends and followers online; DTC genomics can provide a treasure trove of novel content.

If traits should be shared, they could be used in a gaming context between multiple customers. A customer learning about traits A-Z on its own could be bored (especially since their predictive values are limited), akin to reading an astrology report. It would read like a check list of their predicted phenotypes that they probably already knew about. However they may be interested to see how they sit in a spectrum among people they know, and this experience can be gamified.

Product ideas to help you start brainstorming

This set of quantity-over-quality concepts aren’t necessarily any good at all, but is listed here to expand your imagination. If you’re scoffing as you read through this list, ask yourself if would have read the business pitch for Twitter before it was developed, and bought into the idea.

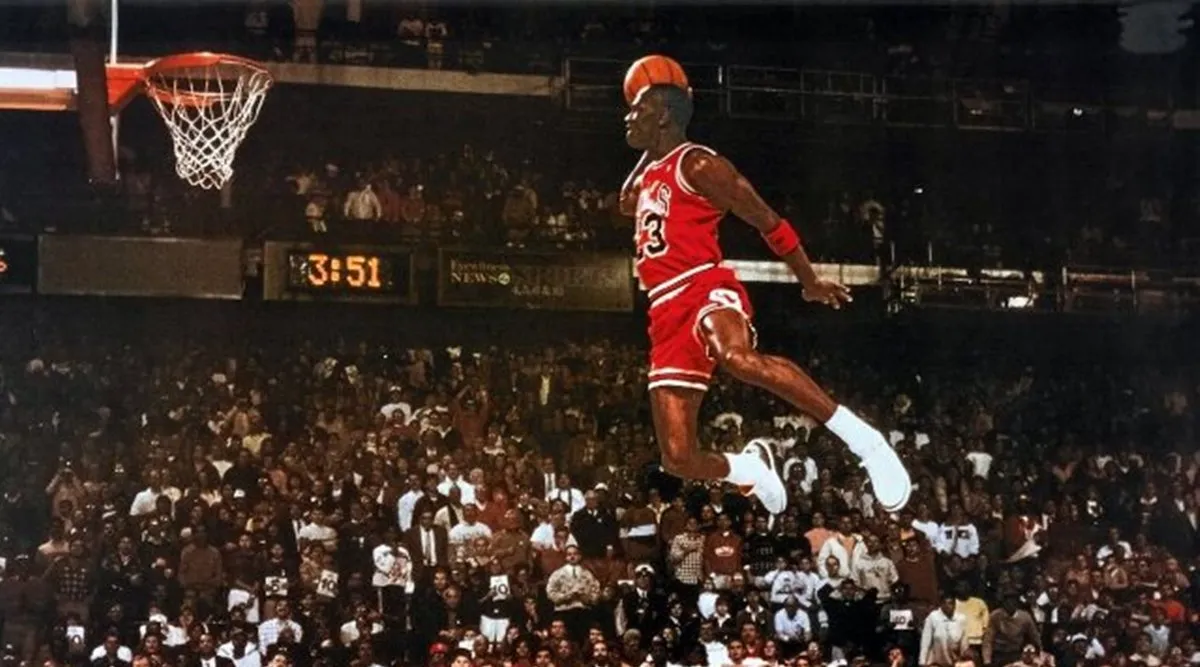

- What do you and Michael Jordan have in common? The basketball legend has been blessed with great genetics along with his work ethics, and you can test to see what traits you have in common – and what you don’t.

- Dating apps that use supposedly shared traits to find what’s in common between two people, or to create some comical conversation points.

- Trivia between friends to find out who is more prone to being sleepy, who can tolerate more alcohol, or who has a larger appetite. Designed for blow-by-blow question and answers to debate fiercely (#myDNAwins or #DNAfail).

- A Nintendo game where your character’s skills are based on your DNA.

- Which siblings do you share more DNA with? Which grandchild has inherited more of a grandparent’s DNA?

- How do your genes compare with others in terms of height or weight? Has your lifestyle helped you beat where you were expected to sit in the spectrum?

- If you’ve got mixed ethnicities, learn which of your facial features are derived from which ethnic group.

- 52 of your traits delivered each week as a post for your social media account to engage your followers.

Conclusion

Genomics is a complex field, with heavy discussion points on how to ensure results are acted on appropriately, managing the possibilities of false positives and negatives, uncertainties around penetrance and expressivity, and with appropriate concern of data misuse. Along with the high costs of sequencing, the subject does not seem designed for entertainment. But this is only the case when dealing with health results and data storage where the stakes are high.

I propose that separate to developments of genomics for improving human health, the stakes could be lowered for entertainment use with an emphasis on social utility. With a plethora of information on the GWAS catalog there is fodder to release a wave of tests that are developed using lean methodologies, with those that establish product/market fit sold at a low cost, and with results delivered for multiplayer user experiences.